Those Little Numbers in Your Bible: A Blessing and a Warning

How Verse Numbers Can Help Us Navigate Scripture—and Mislead Us When We’re Not Careful

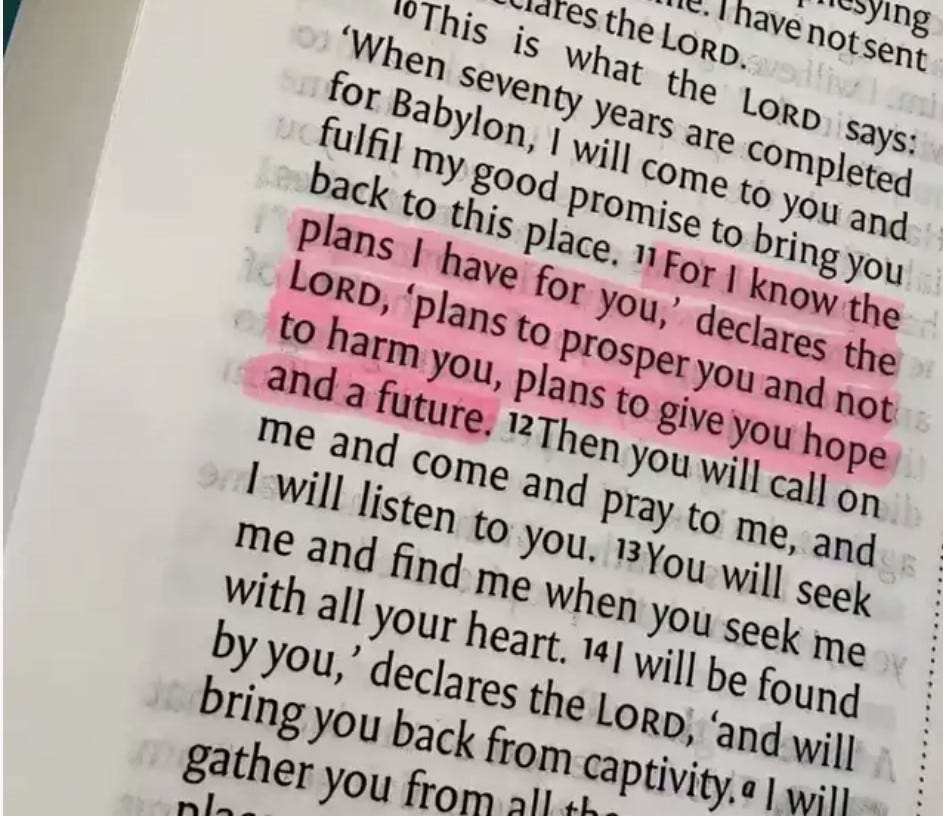

***Notice the pink highlighted section missing the point of the sentences above and below?

Imagine reading a letter from your closest friend...

But instead of reading it as a full, thoughtful message, you cut it into tiny sentences, number them, and start pulling out individual lines as if each could stand on its own. You might find encouragement. You might also wildly misunderstand their intent.

That’s exactly what can happen when we treat the Bible as a collection of numbered “verses” instead of what it truly is—a series of letters, prophecies, histories, poems, and gospels meant to be read in context.

Where Did Chapter and Verse Numbers Come From?

It may surprise you to learn that the original manuscripts of Scripture contained no chapter divisions, no verse numbers, no punctuation, and no paragraph breaks.

Chapters were introduced in the 13th century by Stephen Langton, a professor at the University of Paris who later became the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Verse numbers came later—in the 16th century. The Hebrew Old Testament was divided into verses by a Jewish rabbi named Nathan in 1448. Robert Estienne (Stephanus), a French printer, added verse numbers to the New Testament in 1551.

They were never part of the inspired text.

Now, these divisions have practical value. They make it easier to find passages, study Scripture together, and memorize God’s Word. But they can also be spiritually dangerous if we allow them to shape how we interpret the Bible, especially when they tempt us to treat the text as a fortune cookie—plucking one sentence out and calling it “truth” without regard for context.

Thankfully, more and more publishers are realizing this problem and are offering Bibles (here and here) without the little numbers next to sentences.

Verses That Are Commonly Ripped from Context

1. Jeremiah 29:11 – “For I know the plans I have for you…”

So many Christians quote this verse as a promise of personal prosperity and bright futures.

But Jeremiah 29 was a letter to the Jewish exiles in Babylon. God was telling them that He had not forgotten His covenant people, but they were going to remain in exile for 70 years. The promise was national, not individual. It was covenantal, not a career motivational quote.

Contextual reading restores the meaning: God is faithful to His covenant, even when He disciplines His people. That’s a richer, deeper truth than a vague promise of future success.

2. Philippians 4:13 – “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.”

This verse is slapped on coffee mugs, sports banners, and Instagram bios. It’s often interpreted as a personal empowerment mantra: “I can achieve anything!”

But Paul wasn’t talking about winning football games or getting a promotion. He was in prison. He had just finished saying in verses 11–12 that he had learned to be content in any and every circumstance, whether in hunger or plenty, suffering or abundance.

Contextual reading restores the meaning: The power of Christ strengthens us to endure trials—not simply to achieve success.

Why This Matters for Evangelicals

Evangelicals love the Bible. We study it, preach it, memorize it, and share it. But in our zeal, we must guard against the temptation to atomize Scripture—treating each verse like an isolated truth bomb.

When we do that, we risk:

Creating false theological systems built on out-of-context proof texts.

Missing the flow of the author’s argument, especially in letters like Romans, where Paul builds a case line by line.

Misapplying God's Word to our lives in ways He never intended.

We would never read a contract, a sermon, or a letter that way. Why treat Scripture differently?

What You Can Do

Read big sections at a time. Whole chapters. Better yet, whole books.

Ask: Who was this written to? Why? What came before and after this “verse” I’m quoting?

Beware of “verse devotionals” that don’t walk you through context. Many are more inspirational than biblical.

Treat chapter and verse numbers like road signs—helpful for navigation, but not the destination.

Let’s not be people of “verses.”

Let’s be people of The Word. The whole Word. In all its richness, flow, and context.

“Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved, a worker who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word of truth.”

—2 Timothy 2:15

Instant "like" on this one. I belong to a large-group study (shrinking now as we lose the older folks) where I repeat this over and over again, also, especially in the NT, pointing out the connecting words that relate the statement in which they appear to others.

The chapter and verse numbers are useful as coordinates for locating a passage. I use them for that and ignore them otherwise.

For any kind of deep study, the original languages are important. Essential, I would say. Looking up a lexical form in Strong's doesn't do it, especially for those who don't know what a lexical form is, or a gloss. High-quality original-language commentaries are available, in varying grades according to the reader's proficiency in the languages.

But that would require an awful lot of time, trouble, and expense to go to just to get a good feeling from "reading the Bible". (If Paul can wax sarcastic, so can I.) Although, after being in that large group for several years, pointing out, when necessary what the original texts actually say and how they connect, and what other scriptures they derive from, working from my commentaries and lexicons (electronic media on a tablet PC that I can carry with me), I do get a fair number of inquiries from certain of the group members that want to understand more clearly what they are reading.